Never Forget

As we have seen, all Poe Girls suffer tragic fates. What defines and separates them from each other are their reactions, whether it be passive, thwarting, or, in the case of “Eleonora,” forgiving.

“Eleonora” is the last and only positive version among these stories, featuring a happy marriage unclouded by dark arts or moribund philosophy. However, it’s still a Poe story, so tragedy inevitably ensues. The narrator and wife, Eleonora, are cousins, who live alone (save for Eleonora’s mother) in the idyllic Valley of Many-Colored Grass. They grow up together inseparable companions who fall in love when Eleonora turns fifteen. When their marriage is consummated, there is an outpouring of blooming vegetation throughout the valley: “A change fell upon all things. Strange, brilliant flowers, star-shaped, burst out upon the trees where no flowers had been known before. The tints of the green carpet deepened; and when, one by one, the white daisies shrank away, there sprang up in place of them, ten by ten of the ruby-red asphodel. And life arose in our paths;…”

The newlyweds’ bliss is cut short when Eleonora falls fatally ill. Like Ligeia and Morella, she worries over her death, not its fatality, but whether it will sever their love. She voices these worries during her final throes, vowing she will follow and guard the narrator wherever he goes:

And, then and there, I threw myself hurriedly at the feet of Eleonora, and offered up a vow, to herself and to Heaven, that I would never bind myself in marriage to any daughter of Earth—that I would in no manner prove recreant to her dear memory, or to the memory of the devout affection with which she had blessed me. And I called the Mighty Ruler of the Universe to witness the pious solemnity of my vow. And the curse which I invoked of Him and of her, a saint in Helusion, should I prove traitorous to that promise….

With the narrator’s arduous vow, Eleonora dies peacefully.

Broken Vows

The narrator lingers in the Valley, which seems tinted by Eleonora’s absence: “ a second change had come upon all things. The star-shaped flowers shrank into the stems of the trees, and appeared no more. The tints of the green carpet faded; and, one by one, the ruby-red asphodels withered away; and there sprang up, in place of them, ten by ten, dark, eye-like violets, that writhed uneasily and were ever encumbered with dew. And Life departed from our paths; ” While his homeland withers, Eleonora’s memory thrives and haunts the narrator in “Raven” like sensory:

Yet the promises of Eleonora were not forgotten; for I heard the sounds of the swinging of the censers of the angels; and streams of a holy perfume floated ever and ever about the valley; and at lone hours, when my heart beat heavily, the winds that bathed my brow came unto me laden with soft sighs; and indistinct murmurs filled often the night air; and once—oh, but once only! I was awakened from a slumber, like the slumber of death, by the pressing of spiritual lips upon my own.

The narrator grows weary by all this melancholy and moves to the neighboring royal metropolis where he establishes himself in court and looses himself to decadence. He is taken with a courtly lady, Ermengarde, and marries her: “What was my passion for the young girl of the valley in comparison with the fervor, and the delirium, and the spirit-lifting ecstasy of adoration with which I poured out my whole soul in tears at the feet of the ethereal Ermengarde?” Eleonora is completely forgotten, as is his vow, both relics of a less glorious past.

However, Eleonora has not forgotten her vow. On the narrator’s wedding night, she appears before the newlyweds and surprises her terrified husband by releasing him from the curse: “Sleep in peace!—for the Spirit of Love reigneth and ruleth, and, in taking to thy passionate heart her who is Ermengarde, thou art absolved, for reasons which shall be made known to thee in Heaven, of thy vows unto Eleonora.” And so it ends.

For a Poe story, it is an anti-climatic and rushed conclusion. Poe didn’t buy this ending either. According to biographer Kenneth Silverman in Edgar A. Poe: A Mournful and Never-Ending Remembrance: “Poe considered the tale ‘not ended so well as it might be.’ The problem may have been lack of conviction, for the miserably unconvincing ending suggests Poe’s unwillingness even to imagine absolution from the duty of perpetual remembrance.”1

The story is more a portrait of memory than of love. Poe uses repetition throughout the story to draw parallels between the two amours. With Eleonora, life “arose and departed,” only for him to find life again outside the Valley. His descriptions of Ermengarde’s beauty is as fevered as it was for Eleonora, which begs to question whether either love was the great love, or just true love at that time. The fading of the Valley and the narrator’s escape from its reminders are also commentary on mourning and remembrance. As much as we want to cling to a person’s memory, time passes and our recollections grow vague. Details fade and the order of events rearrange themselves until the image we cling too becomes an overexposed, faded relic that blows to dust in the wind.

To Poe, as Silverman points out, this truth, this failure of mind, was like a second death to the departed. On the other hand, perhaps the ambivalent ending could be viewed as a compromise. As much as we hate to admit it, life does continue and we should not feel guilty to continue with it. Poe biographer Arthur Hobson Quinn takes this view and sees within Eleonora “ Poe’s way of telling Virginia that no matter what happened, she was his mate for eternity.”2 Either way, shortly after the writing of this story, and its publication in late 1841, Poe had to face death in all its various forms explored in that of his young wife, Virginia Eliza Clemm.

The Young Girl of the Valley

Mrs. Poe’s life has been as widely interpreted as her husband’s, but vastly unexplored. Married at 13, dying at 19, dead at 23, fragments of her life and personality are scattered throughout Poe scholarship like Sapphic manuscripts. To date, only one resource, a section entitled “The Real Virginia,” in Susan A.T. Weiss’s The Home Life of Poe seems to be the only source completely dedicated to the poet’s wife. However, it is only three pages long and only scratches the surface. Unfortunately, our focus here must be brief and peripheral.

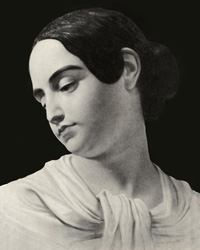

We know enough to surmise she was the Poe-Girl prototype, whether intentional or not. Born August 15, 1822 to Maria Clemm, sister to Poe’s father, Virginia met her first-cousin when he came to live with her family in Baltimore at age 9. Like in “Eleonora,” the two doted on each other, walking “Hand in hand about this valley… before Love entered within our hearts.” She would deliver his love letters to Baltimore amours, and he would take on her education. Companionship bloomed into courtship, and they became engaged when Poe moved to Richmond in 1835. They were married in Richmond on May 16, 1836, when Virginia was thirteen years old, Poe twenty-seven. She was described by friends as dark-haired, fair-complexioned, and violet-eyed. Friends and enemies, like Thomas Dunn English, remembered her “air of refinement and good breeding.”3

We know enough to surmise she was the Poe-Girl prototype, whether intentional or not. Born August 15, 1822 to Maria Clemm, sister to Poe’s father, Virginia met her first-cousin when he came to live with her family in Baltimore at age 9. Like in “Eleonora,” the two doted on each other, walking “Hand in hand about this valley… before Love entered within our hearts.” She would deliver his love letters to Baltimore amours, and he would take on her education. Companionship bloomed into courtship, and they became engaged when Poe moved to Richmond in 1835. They were married in Richmond on May 16, 1836, when Virginia was thirteen years old, Poe twenty-seven. She was described by friends as dark-haired, fair-complexioned, and violet-eyed. Friends and enemies, like Thomas Dunn English, remembered her “air of refinement and good breeding.”3

She loved music. During better times, Poe indulged her by buying her a harp and a piano, which he would often accompany her with his flute. She also sang and on January 20, 1842, a debut performance was held before a small party at the Poes’ Philadelphia residence. What should have been Virginia’s greatest moment became her worst. While singing, her lungs hemorrhaged and she collapsed. Virginia would never sing again.

She was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis, what polite society referred to as “consumption” of the lungs. Consumption in early nineteenth-century America was a death sentence. According to Shelia M. Rothman in Living in the Shadow of Death, it was the cause of one out of every five deaths in the U.S..4 Its symptoms were subtle: hollow coughs, intermittent fevers, hoarseness, feverish skin that appeared as a becoming glow. The disease was torturous in that a sufferer would be completely bedridden and on the brink of death only to resurface from the disease and look perfectly healthy. It was this cycle of hope and despair that Poe, like Egaeus in “Ligeia,” found most horrible in the disease. He writes in a letter dated January 4, 1848:

Her life was despaired of. I took leave of her forever & underwent all the agonies of her death. She recovered partially and I again hoped. At the end of a year I went through precisely the same scene. Again in about a year afterward. Then again—again—again & even once again at varying intervals. Each time I felt all the agonies of her death—and at each accession of the disorder I loved her more dearly & clung to her life with more desperate pertinacity.5

As the letter shows, Poe was well aware of consumption’s horrors. He was more intimate than most, having watched it ravage his mother, foster mother, and brother. He knew, in fact had written implicitly when most minced completely, about Tuberculosis’s last stages. From attending his brother’s deathbed, he knew of the hallowed cheeks and glowing eyes, the knee swelling and stiff joints, the gaunt and emaciated body, the chronic diarrhea, and most of all the relentless coughing that produced profuse hemorrhaging and bloody geysers that almost drowned the sufferer. When Virginia hemorrhaged in January 1842, he knew her future only too well.

Even so, Poe was in denial of Virgina’s illness. He refused to speak of it. When he did address it, he denied the disease by claiming she had merely ruptured a blood-vessel. Perhaps he was riddled with guilt from his women stories that seemed to have predicted her fate and placed in stark contrast the reality that, unlike those women, Virginia would not return.

Virginia suffered through the disease for five years, her suffering heightened by her husband’s therapeutic drinking binges, and her Eleonora-like worry over his fate. On her deathbed, she reenacted Eleonora’s forgiveness by asking lady friends to care for him, like Mary Starr, who Poe courted when Virginia was a child: “I had my hand in hers, and she took it and placed it in Mr. Poe’s, saying, ‘Mary, be a friend to Eddie, and don’t forsake him; he always loved you—didn’t you, Eddie?”6 She died on January 30, 1847 and became the consummate Poe Girl.

While faint echoes of the Poe Girl reappeared in Poe’s poems like “The Raven” and “Annabel Lee,” those women never lived to die like Ligeia, Berenice, Morella, and Eleonora. The poems’ shadows exist in a state akin to memorial statuary: static, melancholy, and eternally beautiful. The Poe Girl however is something more terrible. She lives and breaths and occupies her husband’s lives, be it as an object or a superior in arcane knowledge and passionate love. She is flawed, powerful, and intimidating. While she will meet the same fate as Ulalume or Lenore, she does not die quietly. Whether it is to forgive a lover, she inevitably returns, making her death not a sad instance, but a philosophical positioning of what love, the afterlife, identity, and the soul could mean.

1 Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. New York: HarperPerennial. 1992. P. 170.

2 Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: John Hopkins Press. 1998. P. 329.

3 Ibid. P. 347.

4 Rothman, Shelia M. Living in the Shadow of Death: Tuberculosis and the Social Experience of Illness in American History. New York: BasicBooks. 1994. P.13.

5 Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: John Hopkins Press. 1998. P. 347.

6

Thomas, Dwight and Jackson, David K. The Poe Log: A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe 1809-1849. New York: G.K. Hall & Co. 1987. P. 683.

S.J. Chambers has celebrated Edgar Allan Poe’s bicentennial in Strange Horizons, Fantasy, and The Baltimore Sun’s Read Street blog. Other work has appeared in Bookslut, Mungbeing, and Yankee Pot Roast. She is an articles editor for Strange Horizons and was assistant editor for the charity anthology Last Drink Bird Head.